With the death of David Sutcliffe one of the titans of the United World College movement has been taken from us. His achievements for each of three different Colleges were so fundamental to their success that any one of them amounts to more than a normal lifetime’s work.

Born in 1934 in London to the family of a doctor in Guernsey in the Channel Islands, David spent the war years in England while Guernsey was under German occupation, though his father remained to provide medical services to the community. David recalls that when he returned after the war ‘Like many others of my age, I can only be grateful to my parents who allowed me without reservation to cycle all over the Island of Guernsey at the age of eleven and twelve with a powerful air rifle strapped to my back, to canoe on the open sea, to climb the cliffs for bird-nesting, to clamber out to rocks at low tide, remain there all day and return in the evening when the tide had again fallen with our catch.’

After Sedbergh, a rather rigorous boarding school in the north of England, David gained a degree in Modern Languages at Cambridge University, where he was a very successful rugby player. (By the time he got to Atlantic College he had decided, along with Desmond Hoare, that team sports, if played at all, were no match for the rescue services as a preparation for life). David then taught for four years at Salem, the school in Baden-Württemberg where he met his wife Elisabeth who was also teaching there, and then for a year at Gordonstoun in Scotland, both founded by Kurt Hahn.

No doubt through his connection with Kurt Hahn, David was involved in the planning of Atlantic College before it opened in 1962 and became a member of the founding staff. He taught German (until 1972 the College prepared its students for British A-level exams) but that was only a small part of his life at the College. Under the leadership of Rear-Admiral Desmond Hoare, the inspirational first Headmaster, the College was actively developing sea-rescue services : David first led the Canoe Lifeguard Unit, initially separate from, but working with, the Beach Lifeguards before the two merged into the Surf Lifesaving Unit. He quickly became a very proficient surf canoeist and this determination continued when he took over from Hoare the Inshore Lifeboat Station, for many years the best- known feature of the College. He soon became a housemaster and then Director of Studies and took part in early discussions about an ambitious new curriculum which was to become the International Baccalaureate.

In 1969, as Desmond Hoare moved from being Headmaster to Provost (a post he held until 1973 before retiring to Ireland) David succeeded him not only in charge of the Rescue Boats but also as Headmaster. The College had already gained a reputation for several radical pioneering educational initiatives, many inspired by Kurt Hahn, some widely copied but most regarded in their time as extraordinarily ambitious and often risky and controversial. Under David, always driven by the College mission and with the experience of students as his top priority, these continued to develop and expand. Among his own many innovations were setting up the summer programme of the Extra- Mural Department which welcomed scores of young people, mostly groups from inner cities, to the College during the long holiday with former and present students running most of the activities ; and the restoration of the Cavalry Barracks and turning them into a centre for the Youth Training Scheme for unemployed young people. He also gave a strong impetus to programmes in Music and Art and the development of the Tythe Barn as a local Arts Centre.

David was vigorous in his support of the International Baccalaureate (Desmond Hoare, while appreciating its international emphasis, had been the first to worry that the time students needed to spend on preparing for exams would detract from their more important educational experiences). All teachers were encouraged to participate in IB developments including the creation of the new syllabuses, several of which, such as Peace Studies, were developed wholly at the College, some drawing support from outside bodies. Many meetings were held at the College, and in 1973 more than half the total number of IB Diploma candidates in the world were from Atlantic College. When the fledgling IB was in grave danger of financial collapse in 1976 David, in a meeting in London which led to the setting up of a permanent association of the Heads of IB Schools, persuaded the heads of other IB schools – still very few - to join Atlantic College in contributing funds to save the whole enterprise from collapse. His active support of the IB continued in his later roles as Vice President of the Council of Foundation and Deputy Chair of the Executive Committee.

In 1982 David left Atlantic College to become the founding Rettore (Head) of the United World College of the Adriatic in Duino, near Trieste. For several years he had taken part in the planning : as in the creation of other United World Colleges there had been setbacks and delays along the way, and he always recognised the vital contributions of Gianfranco Bonetti, Corrado Belci, and Giorgio Pontoni, without whom the College would never have come into existence. The school admin buildings and classrooms were not ready by the time the College opened and the first year was spent in the Hotel Europa, along the coast on the way to Trieste, which provided not only the accommodation but also the teaching facilities until the College had access to classrooms and science labs in Duino. In deliberate contrast to the campuses of other UWCs, the students eventually moved into residences around the village to become part of the local community life. This enabled a more flexible routine than at Atlantic College but David brought the same energy and spirit as he had always shown and the College, taking full advantage of its location in an area rich in history and culture and close to the mountains, immediately flourished.

David was always proud that in his time virtually all students were offered places on full scholarships. The generous financing of the College by the Italian authorities which made this possible was subject to occasional political uncertainty and this gave David some nervous times – in 1994, for example, there was real doubt about whether a new intake of students should be recruited, until new funding was agreed just in time. David’s facility with languages was a major asset and his rapid mastery of Italian was crucial to his dealings with supporters, politicians, academics, intellectuals and other visitors to the College, not to mention local people in Duino.

David travelled widely in the Balkans on behalf of the Adriatic College, selecting students and establishing significant contacts as he went. The Yugoslav wars of the early 1990’s (during which he had been a keen supporter of student work in refugee camps in Slovenia and Croatia) and the continuing discord which followed made a big impression on him. In his 2000 speech in Prague marking the opening of the Adriatic College - an annual event held after the beginning of each academic year and often in a city well away from Duino - he said “It must become our joint task to take international education not to where it can be afforded, but to where it is really and urgently needed. It is here that I see the evolving mission of the Adriatic College.”

What happened after that is characteristic of David’s pragmatic idealism and personal commitment. Some weeks later he met Pilvi Torsti (a Duino alumna, then working on her PhD on divided education in postwar Bosnia and now State Secretary in Finland) who challenged him by asking whether he was up to the task he had just set up in Prague. David responded by inviting Pilvi to his office two hours later. Meanwhile he had drafted the first ‘ideas paper’ for Bosnia. Just a few months later he travelled with Antonin Besse (who had previously bought St. Donat’s Castle for Atlantic College and had been instrumental in setting up the Adriatic college) to Sarajevo. “We are two old men worried that UWC should remain a movement”. Tony Besse introduced them as they met Pilvi at the airport. The group of “three musketeers” was born.

So, standing down in 2001 after nineteen years as the Adriatic College’s Rettore, David devoted enormous time and energy to establishing a new kind of UWC in Bosnia, which had suffered immensely during the war and was recovering only very slowly. “Can the United World Colleges contribute”, he wrote, “after the cessation of conflict, to the rebuilding of civic society on the ground ? Are we right within the UWC to sense a renewed need for an idealistic target that might initially seem to be beyond our grasp ? Is there a real role for international education in societies struggling to regain their balance after conflict, the roots of which are still present ?”

The first idea was to work in Sarajevo. David himself studied the potential of several war-destroyed buildings for the college. He was particularly keen on one ruin that was owned by Sarajevo brewery – perhaps because of good beer but also as the same brewery had provided fresh water for the city during the entire siege of 1992-95.

David developed a plan that was three-fold from the start: to set up a demonstration of international quality education, to support the educational reform in Bosnia as he had seen happening in Slovenia, and to set up a major teacher training programme.

David and his musketeer team used all possible contacts to develop a strong enough proposal which was finally called the UWC-IBO Initiative in Bosnia-Herzegovina. It included the UWC College in Mostar, partner IB schools in Sarajevo and Banja Luka and components for teacher training and development of post-war education system. Through personal letters David secured critical early support from Antonin Besse (“He was not happy about the letter but he agreed”), Adriatic College and the Finnish Cultural Foundation.

The college was to share a building with the Mostar’s historic Gymnasium which had been damaged during the war and was then in “no man’s land”. The condition for the renovation of the building was the return of all national groups. For that UWC was critical.

There were enormous financial and other difficulties but David’s determination steadily overcame them and a strong group of supporters was marshalled including Kofi Annan, minister Elisabeth Rehn from Finland (previously the UN Special Rapporteur for Human Rights in Bosnia and Herzegovina), George Walker (then the IB Director General), professor Lamija Tanovic from Sarajevo, Jasminka Bratic from Mostar, and the government of Norway. David personally persuaded a growing group of local and international supporters - too many for all to be listed here - to commit to the project. Like so many students of David in Wales and Duino before, these individuals, inspired by his example, found themselves doing more than they had known they were able to.

David often recalled an early supporter, a Bosnian politician, who said to him after one complex meeting “It is very difficult to succeed here but if you do it is a great victory”. He was also moved when he learnt how people in Bosnia and Herzegovina had concluded that he was different from most ‘internationals’. The UWC team was pushed by OSCE to start the Mostar College in 2004 with just 6 months of preparation period (including renovation!). Saying no seemed at the time the end of the great project after three years of trying. “At that moment, I realised that you were serious and with strong commitment and integrity” a local key supporter later told David.

But under David’s leadership the three musketeers did not give up and the UWC in Mostar – a lighthouse for Bosnian education as the Norwegian Ambassador called it - opened in 2006 and has thrived since then with students from each of the three main groups in Bosnia and a strong complement of international students, with emphasis on conflict and post-conflict countries. Students live in residences within the city, undertake a wide variety of community services, and do their best to integrate with the local community – all while achieving excellent academic results. For a long time it was the only school in the country in which Serbs, Croats, and Bosniaks (Muslims) shared a classroom.

The facilities of the Mostar UWC were to be modest without much capital investment. David was ready to propose a three-year project first after which the work would be evaluated. He was often criticised for this approach but it really was yet again an example how he would come up with a practical solution when a good idea was otherwise at a risk of fading away. In this way initial donors could commit themselves and the work got started.

As a result of its success and the project’s relevance David himself saw and many supporters witnessed, the work continued under David’s leadership to raise funds to keep Mostar going. Thanks to this work, the College which for the first 10 years was run like a start-up, is slowly stabilizing as an institution and making it possible to start focusing more on the wider impact in the region and in other post-crisis regions which was what David had always intended.

Foremost among the qualities which made David a great school leader was that he did not just talk about the UWC mission – he lived it ; the first time I witnessed this myself, less than two weeks after I joined Atlantic College, was his own desperate but vain effort to revive a fisherman who had fallen from a rock into the sea off Monknash Cwm after his body was found by the College’s student rescuers who abandoned their canoes and waded in the sea as the tide went out. Soon after that he led a group of staff and students to work throughout the night after the disaster at Aberfan in the Welsh valleys.

He encouraged all those who worked with him to develop their skills and to come up with ideas of their own : if a colleague came to him with a proposal in line with the UWC mission his reaction would be to say ‘yes – go for it, and I will support you provided you can make it work’ and to carry on doing so. And he took pleasure in the successes of his colleagues, both at the time and in posts they went on to later. Always straightforward with everyone – students and teachers alike – if he felt you were not pulling your weight or were doing something foolish he would make his views very clear (former colleagues may remember finding with apprehension a blue note in their staffroom letter box, always a sign that one had done something of which David disapproved – the more serious the matter the smaller the piece of blue paper).

As for students, his time was never so precious that he was not available. David quoted Kurt Hahn in an article in the International Schools Journal describing his criteria for school headship: “respect is not enough; affection is not necessary ..... what is wanted is trust; trust that a boy (Hahn had known only boys in his own schools) be heard in patience by an unoccupied man, that he will be understood if he does not say much, that nothing he says will be misused ...”

Since he died, hundreds of former students have joined Facebook pages including one set up by his old Duino colleague Manuel Fernandez, and scores have recorded their memories of David, many telling how he changed their lives, even in a single conversation. A regular refrain is that though he seemed stern and unapproachable, a student would be taken aback by how much David knew about them, and how a single sentence of encouragement or advice could have a dramatic effect. Clearly, he had a great influence on many lives. It will be better to read those comments directly, but the following one is perhaps typical :-

Caro Rettore, you were like a father to us. Firm when it mattered but forgiving when it mattered more. Leading by example, as a principle. You have encouraged us at the right moments and lovingly corrected when we should have known better. You had deep respect for each and every member of the community and always knew how to strike the right balance between common good and good of the individual students or teachers. You have shown us that dreams can be lived and that feet on the ground are a great help at that. You are responsible for my best educational experience as well as the best travel experience.....

David had a strong sense of adventure. He had been introduced to sailing as a young boy in Guernsey and in the very early 1970’s he bought a Contessa 26 yacht which he called Lady Anne of St. Donat’s and kept in Barry Harbour. He began taking family, colleagues, and students on increasingly long voyages, sometimes as far as Spain, and by 1976 was ready to enter the Observer Single Handed Trans-Atlantic Race. The College Governing Body had granted him a sabbatical – though Sir George Schuster, the doyen of AC Governors, who knew little of the sea, told Colin Reid (who assisted him with his autobiography) that he thought it "grossly irresponsible of the Headmaster to put himself at such risk". Minor problems included appendicitis a few weeks before the event and the need to rescue the IB from financial collapse by calling the meeting mentioned above just two days before the race began in Plymouth. This was before the days of GPS so navigation had to be by sextant and compass ; he had no radio contact so Elisabeth and her family only rarely knew, when his position was reported by a passing ship, where he was, or indeed that he was still alive. Weather for the 1976 race proved to be unusually ferocious, leading to two fatalities and 47 yachts out of 125 starters having to be rescued or to retire. David crossed the finish line in Newport, Rhode Island, 46 days after setting off, his boat one of the smallest to complete the race. His account of the voyage – during which he read all of Shakespeare’s plays, Tolstoy’s War and Peace, and many more great works - makes fascinating reading.

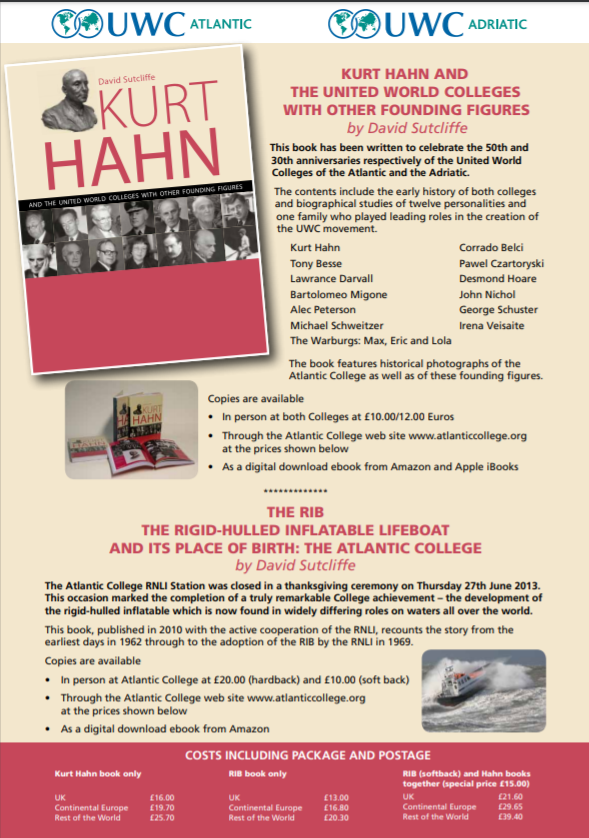

David was a prolific and brilliant writer. Among his books, in addition to those already mentioned, his published works include ‘Kurt Hahn and the United World Colleges with Other Founding Figures’, ’The RIB’ (a superb account of the development of the Rigid-Hulled Inflatable Lifeboat at Atlantic College), and a pamphlet on ‘The Early Atlantic College and the Birth of the International Baccalaureate’. He spent several years working on an ‘official’ biography of Kurt Hahn and it is much to be hoped that someone will take this on and complete the work.

One can follow the progress of David’s thinking about how the UWC movement should develop through the many speeches he delivered or articles he wrote, mainly over the last twenty years of his life. A recurrent theme is that individual Colleges and the movement as a whole should remember the fundamental aim of the project – an education to meet the needs of the times – and be ready to address those needs, and not allow the project to become institutionalised. At the Duino 2010 reunion he observed that ‘we must all be conscious of the classical fate of progressive schools. They are founded to advocate and to demonstrate educational reform as a matter of principle. If unsuccessful, they disappear and are forgotten. If successful, their ideas are absorbed into the mainstream....”

In a speech that David said he would have delivered at the 2016 Duino reunion if he had attended, David noted that “UWC Mostar has just celebrated its 10th anniversary. It is no longer a project. It is now an institution. A project’s aims speak for themselves. An institution’s aims require constant re-examination and redefinition. The Atlantic College was not founded to educate some 150 international teenagers each year. It was founded to create and to demonstrate a form of ‘education adapted to meet the needs of our time’. UWC International (a movement?) is of course also now an institution”.

Though David himself was the Executive Director of the United World Colleges between 1994 and 1999, while simultaneously running the Adriatic College, it is not surprising that his bold ambitions and clear views of the UWC mission, always strongly expressed, sometimes put him at odds with the International Office in London in his later years.

David’s rather subtle sense of humour was a surprise to those who saw him only in his serious moments. He was a fine raconteur when relaxed and quite willing to make a fool of himself on stage - his occasional public performances, such as his role as the village idiot in the 1990 Duino staff production of The Murder of Maria Marten, proved memorable. Though his formal speeches – and he was invited to give a great number - invariably had a serious and often uplifting message he liked to include the odd humorous message or anecdote. He would sometimes begin, depending on whom he was addressing, with some version of ‘The three most difficult things are to climb a fence that is leaning towards you, kiss a girl who is leaning away from you, and say something original about international education’.

For a man of such accomplishment he was extraordinarily modest. He almost never talked about his transatlantic sailing adventure and even today very few know that in 2000 the President of Italy conferred on him the title of Grande Ufficiale Ordine al Merito della Repubblica Italiana, an extraordinary honour especially for someone of foreign nationality.

Above all David was a family man. His wife Elisabeth was his first supporter in everything he did and was famous both at Atlantic College and in Duino for the warm hospitality she provided for an almost continuous stream of visitors, often including actual and potential supporters, and for her generous dinners for colleagues and friends. Her energy in all of this was admired by all who knew her. In 1993, David and Elisabeth suffered the tragedy of losing their youngest child Edward, who was on the cusp of a promising career in the Metropolitan Police, after a long illness. Their pride in Michael and Veronica and their families has been a joy to their friends. One of David’s last pieces of writing, in German, was a history of Elisabeth’s distinguished family.

And so the UWC movement says farewell to a towering figure who played an absolutely key role in the life of three of its colleges and had an unparalleled influence on the movement as a whole. That influence will continue - it will be part of his legacy - because the need for an “education adapted to meet the needs of our time” is more urgent and necessary than ever.

Andrew Maclehose

November 2019

Notes

1) The information on UWC Mostar was provided mainly by Dr. Pilvi Torsti

2) Colin Reid and Henry Thomas made valuable comments on an earlier draft

3) Three books written by David and referred to in the text are available from Atlantic College

David B. Sutcliffe's family has sent the following message to the UWC community: "We have been greatly moved and are immensely grateful for all the wonderful messages, memories and thanks to David, which have comforted and supported us at this sad time. David’s funeral will take place at All Saints’ Church, 122-122A High Street, Lindfield, Haywards Heath, West Sussex, RH16 2HS on Friday, 29th November at 11.30 am. Family and friends are welcome. There will be a reception afterwards at The Tiger (church hall) next door. Family flowers only. According to David’s wishes, any donations should please go to the UWC Mostar Endowment Fund for student scholarships. It is thought that there will also be a memorial event for David held in the New Year. With love from Elisabeth, Michael, Veronica and families.’

.png)

What happened after that is characteristic of David’s pragmatic idealism and personal commitment. Some weeks later he met Pilvi Torsti (a Duino alumna, then working on her PhD on divided education in postwar Bosnia and now State Secretary in Finland) who challenged him by asking whether he was up to the task he had just set up in Prague. David responded by inviting Pilvi to his office two hours later. Meanwhile he had drafted the first ‘ideas paper’ for Bosnia. Just a few months later he travelled with Antonin Besse (who had previously bought St. Donat’s Castle for Atlantic College and had been instrumental in setting up the Adriatic college) to Sarajevo. “We are two old men worried that UWC should remain a movement”. Tony Besse introduced them as they met Pilvi at the airport. The group of “three musketeers” was born.

What happened after that is characteristic of David’s pragmatic idealism and personal commitment. Some weeks later he met Pilvi Torsti (a Duino alumna, then working on her PhD on divided education in postwar Bosnia and now State Secretary in Finland) who challenged him by asking whether he was up to the task he had just set up in Prague. David responded by inviting Pilvi to his office two hours later. Meanwhile he had drafted the first ‘ideas paper’ for Bosnia. Just a few months later he travelled with Antonin Besse (who had previously bought St. Donat’s Castle for Atlantic College and had been instrumental in setting up the Adriatic college) to Sarajevo. “We are two old men worried that UWC should remain a movement”. Tony Besse introduced them as they met Pilvi at the airport. The group of “three musketeers” was born.

David was a prolific and brilliant writer. Among his books, in addition to those already mentioned, his published works include ‘Kurt Hahn and the United World Colleges with Other Founding Figures’, ’The RIB’ (a superb account of the development of the Rigid-Hulled Inflatable Lifeboat at Atlantic College), and a pamphlet on ‘The Early Atlantic College and the Birth of the International Baccalaureate’. He spent several years working on an ‘official’ biography of Kurt Hahn and it is much to be hoped that someone will take this on and complete the work.

David was a prolific and brilliant writer. Among his books, in addition to those already mentioned, his published works include ‘Kurt Hahn and the United World Colleges with Other Founding Figures’, ’The RIB’ (a superb account of the development of the Rigid-Hulled Inflatable Lifeboat at Atlantic College), and a pamphlet on ‘The Early Atlantic College and the Birth of the International Baccalaureate’. He spent several years working on an ‘official’ biography of Kurt Hahn and it is much to be hoped that someone will take this on and complete the work.